By 1921, the National Council and Presiding Bishop officially begin conversations about adopting armorial bearings with a proposed design submitted by la Rose. No action is taken and a committee is appointed to study the design and consider various proposals in preparation for the 1922 General Convention. We end the first portion of this article with the 1922 General Convention where the first official proposal for arms is submitted, but ultimately the General Convention took no action on the matter (General Convention, 1922).

Following an unsuccessful attempt during the 1922 General Convention, Baldwin works behind the scenes through his own diocese to generate the next step in the story. At the 1925 General Convention held during October in New Orleans, the 1922 Joint Committee on Flag and Seal would be formally disbanded and a new resolution passed authorizing a new Joint Commission on Flag and Seal. Baldwin introduced the following resolution before the House of Deputies championing his cause:

While it appeared that Baldwin would gain momentum during the convention, ultimately no proposed design was introduced.

Three years later, the General Convention of 1928 would appoint additional members to the commission, adding most notably Ralph Adams Cram. Yet, no proposals or action regarding designs for the church flag or seal were taken during convention that year (General Convention, 1928).

From 1928 until the 50th General Convention met in 1931, there is seemingly no published information concerning design proposals or behind the scenes work regarding a flag or seal. During the 1931 General Convention, Baldwin puts forth the following design proposal on behalf of the Joint Commission:

The design resolution before the convention was presented as a flag for consideration. Pending adoption, the blazon would be rendered into a coat of arms surmounted by a bishop's mitre with a key and crozier behind the shield in saltire. On a ribbon below the shield would bear the motto, "go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel," and the whole arrangement would be set within a vesica piscis with the legend, "Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America" (General Convention, 1931, 338). To visualize the Joint Commission's 1931 proposal, I've emblazoned the arms as an armorial flag below.

By the time the Episcopal Church gathers in Cincinnati, Ohio for its 52nd General Convention during October 1937, the Joint Commission is serious about getting a design adopted. Since discussions began in 1921, the Church has now invested 16 years on the matter of selecting a flag and seal.

The Joint Commission, in its initial design resolution, proposes the following blazon for a new church flag:

From this blazon, those possible objections raised concerning the 1931 design proposal containing the blank open book and blue eagle were seemingly corrected. There is no justification provided for using a cross quadrate or fimbriating the ordinary; the cross quadrate was most likely the commission's solution to better contain the open book. Fimbriating the cross allows the the use of a red cross by adding a white line when the field is blue--avoiding the color-on-color rule of heraldry. The eagle and olive branch were removed, the blank open book is now identified to be the Book of Common Prayer, and nine white/silver stars are arranged in saltire to historically represent the original founding dioceses.

To visualize the first 1937 design proposal, I've created an emblazonment below.

As soon as Baldwin submitted the Joint Commission's resolution containing the first design to the House of Deputies, it was amended and sent back to the commission to report later during the convention (General Convention, 1937, 251-252). There is no data cited as to the cause for the amendments, much less what those amendments were. It is possible that design revisions were requested. With Baldwin's leadership and utter determination to see a design adopted, the commission submitted a revision of the flag's design to the Deputies with the following blazon:

The revision made by the Joint Commission maintained the blue field for the flag and replaced the red fimbriated cross quadrate with a simpler red fimbriated cross. The inscribed book was removed as the central charge and the nine white/silver stars are given prominence in the overall design.

To better visualize the second design proposal in 1937, I've emblazoned the proposed flag below.

Considering all proposed designs from 1921 to 1937, we begin to understand how the flag's design would evolve to its final form. Three design elements seemingly win approval, or rather keep emerging throughout this laborious process: (1) the red cross of St. George, (2) the number nine to represent the founding dioceses, and (3) incorporating the Scottish heritage by employing the saltire in various forms.

The final resolution which sealed the fate of the Joint Commission's second design came from the House of Bishops, adopting, "Resolved, the House of Deputies concurring, that the design submitted be approved after it has been approved or modified by such experts in heraldry as your Committee may be able to consult" (General Convention, 1937, 254). While the second design would gather momentum, possibly representing the closest proposal for adoption yet, the General Convention did not vote on adopting a flag or seal in 1937. The struggle for Baldwin would continue.

Since 1672, the dukes of Norfolk have maintained a hereditary position as an officer of state in the United Kingdom, that of Earl Marshal. Fox-Davies (1978) notes that not only is the Earl Marshal head of the College of Arms in London, but to his office is delegated all control of armory in the United Kingdom save those particulars held in right by the Crown. Therefore, whenever the Earl Marshal issues a warrant pertaining to heraldry, the warrant becomes the law of arms.

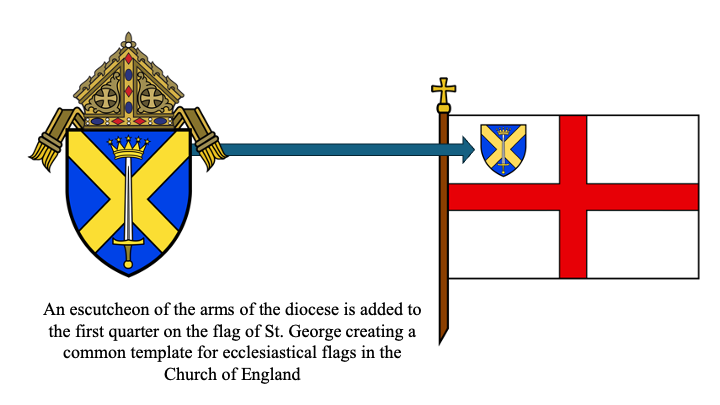

The timing of the warrant is auspicious, especially considering the Episcopal Church's plight to adopt a flag. The warrant sets precedence for how the Church of England would represent unification by way of the red cross of St. George and provide suitable differencing through the dexter canton (or the first quarter).

Current articles on the history of The Episcopal Church flag fail to consider the Earl Marshal's Warrant of 1938 as a critical data point likely influencing what would become the church flag. Throughout the 1930s, all design proposals submitted before General Convention were rendered as flags, likely influenced by Baldwin. While no data exists at present regarding la Rose's knowledge of this warrant, there is a high probability that the herald would have been alerted to its publication. Given the subject of the Earl Marshal's warrant of 1938, the timing and relevance for the Episcopal Church would have most assuredly caught the attention of many interested parties.

Redemption and Adoption: 1938-1940

At the close of the 1937 General Convention, a directive to have the second design approved or modified by an expert on heraldry was issued to the Joint Commission. Which expert would the commission seek out? Why would la Rose consider such a commission from the Church given the history of rejected proposals regarding the matter? Who could possibly convince la Rose to become involved with the project? Perhaps we need only look to his heraldic partner-in-crime of 33-years, Ralph Adams Cram. Cram's appointment to the national commission in 1928 becomes more relevant now in the years following the 1937 General Convention, where he is listed as an active member of the Commission on Church Flag and Seal (General Convention, 1937, x). It is my view that Cram's 10-years of service on the Commission, coupled with the House of Bishop's directive for expertise, may have likely propelled the Boston architect to ask la Rose for help.

|

La Rose would have likely added his favorite version of the mitre from the

1515 herald's role as the external ornament

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2024 |

No one, save Cram, could have otherwise convinced la Rose to re-tangle himself with Episcopal Church committees and armchair enthusiasts. If my assertion is correct, Cram finds his ultimate redemption in the world of heraldry following his troublesome article of 1901. For if Cram failed to convince la Rose to accept this commission, the Episcopal Church would not have its beloved symbol known and cherished today.

Based on the second design proposal from 1937 along with the Earl Marshal's warrant from 1938, la Rose had plenty of subject matter to consider for a new design. Taken together, these two data points effectively reveal how the final version of the Episcopal Church's flag and arms were logically constructed by la Rose. Perhaps it is for this reason--an easily and readily apparent design--made la Rose's decision to accept the commission more palatable.

The simple red cross of St. George explains itself and its connection to the Church of England. La Rose changed the field in the dexter canton from white/silver to blue, as the blue field was used in both 1937 flag proposals. For the final design component, the herald had a clever plot twist in mind, showing la Rose's mastery of how abstraction could tell a deeper story in corporate heraldry.

|

Click graphic to enlarge

Illustration rendered by Chad Krouse, 2024

|

While maintaining the saltire arrangement for nine charges, la Rose replaced the stars with cross crosslets and added the design to the first quarter. From previous writings, la Rose reserved the star as a symbolic charge for either a state or the Blessed Virgin Mary. In the case of the Episcopal Church's coat, the star as a charge does not make sense. In one simple canton, la Rose illustrated the nine founding dioceses of the Episcopal Church, its aim for the heavenly Jerusalem with the cross crosslets, and honored the Scottish Episcopal Church's ordination of its first bishop

Samuel Seabury (1729-1796) through the saltire arrangement. La Rose's finished product would truly represent a "cross in national colors."

.png) |

Baldwin's handmade prototype of the proposed flag

Image source: Diocese of Long Island |

No other heraldic designer could have incorporated such history and meaning into one coat of arms, much less render the design in the simplest form possible--the previously proposed designs over the years attest to this fact. Without any precise dates, it is likely the design work took place between 1938 to as late as the Spring of 1940, as any final rendering would have to be in place well before the convention in October. There would be a natural time lag due to mailing correspondence to multiple parties and so forth.

During October 1940, the General Convention convened in Kansas City, Missouri and the commission would submit la Rose's design for consideration. Commission Chair, the Rev. Arthur B. Kinsolving (1884-1964), informed the governing body that the commission had not met since the 1937 convention, noting that members were scattered across the country and several resigned. Kinsolving reports:

"On accepting the chairmanship, I felt the wisest course of procedure would be to secure expert advice in this highly technical field so as to avoid the glaring heraldic errors appearing on some of our diocesan shields. Accordingly, I consulted Mr. Pierre deC. laRose, of Harvard University, a member of its Standing Committee on Arms, and recognized as probably the leading authority on ecclesiastical heraldry in this country.

"He has graciously and generously given of his time and thought and his opinions have received the hearty approval of your Commission. Of the design we are submitting, Mr. Ralph Adams Cram writes: 'I am very pleased with this. I can give it my full approval.' Another of our most expert members in this field, Major Chandler, writes: 'I am sure any delineation--shield, seal or flag--which Mr. laRose may make will be unassailable heraldically and any composition of which Mr. Cram approves will be beyond question artistically'" (General Convention, 1940, 287).

The commission proposed the following blazon: "Argent a cross throughout gules, on a canton azure nine cross crosslets in saltire of the field" (General Convention, 1940, 288). It is unclear if la Rose's design proposed before the convention was rendered as a shield or flag.

Given Baldwin's hand-sewed prototype seen above, the flag design was likely intended to be displayed vertically as the red cross of St. George is placed off center.

_____________________________________

ORIENTATION & DISPLAY

The flag's orientation dictates the placement of the red cross as seen in the illustration above.

When the armorial flag of the Episcopal Church is flown vertically and suspended from a pole, the red cross is off center on the field and closer to the hoist. The hoist, or left side of the flag, secures the flag to a rope and/or pole thus allowing it to be hoisted into the air. Vertical displays of flags and banners are often seen inside cathedrals and large parish churches where open and available (vertical) space is not a problem.

Whereas when flown and displayed horizontally on a traditional flag pole, the red cross is centered on the field. Many parishes innocently purchase the wrong version of the armorial flag--vertical use--and display it horizontally, tucked into a corner somewhere in the sanctuary.

|

Armorial flag of the Episcopal Diocese of Central Florida

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

One exception to the rule regarding the red cross can be found in Florida. The Diocese of Central Florida adopted an armorial flag in 1981 based on its arms, but placed the red cross of St. George off center in the field and closer to the hoist (De Kay, 1993, 32). We don't know if the flag design was based on a possible vertical display.

|

Arms of the Episcopal Diocese of Central Florida

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

_____________________________________

With seemingly little fanfare, the commission's proposal is adopted and the Episcopal Church, at long last, has a properly designed coat of arms.

The adopted arms of the Episcopal Church are both simple and clear, providing the national church with a beloved symbol still in use 83-years later. In many ways, the final design is the perfect ending to la Rose's stormy involvement with the Church. Through this one coat of arms, we see la Rose at the height of his heraldic powers. Perhaps no ecclesiastical or corporate coat is more widely recognizable in the US today than the arms of the Episcopal Church.

With his work for numerous dioceses, several cathedrals, and now a national coat for the Episcopal Church completed and in good order, la Rose would hang up his herald's tabard to rest eternally in 1941--a year following what could arguably be one of his greatest designs.

Post-1940 Heraldic Developments

Baldwin's 22-year crusade for a national church symbol comes to a successful close. For his tenacity and perseverance, Baldwin deserves much credit for his contributions in the struggle to adopt such a symbol. With his ministry concluded, Baldwin would die two years later in 1942 with his place cemented in the Church's history.

Cram's redemption in this story, in some ways, is tied to his heraldic partner la Rose. While Cram would bow to the herald on matters of ecclesiastical heraldry, Cram's involvement in how the Episcopal Church adopted arms--most likely enlisting la Rose's help--is cause for vindication. Cram would also die in 1942 and commemorated on December 16th in the Episcopal Church's liturgical calendar.

During the General Conventions of 1943 and 1946, the Church revisited the role and responsibilities for the office of Presiding Bishop. Previously, the Presiding Bishop had to maintain oversight for his diocese in addition to serving his national role (Luce, 1958). When the canons changed allowing the new Presiding Bishop to resign his see, the need for an official seal became apparent. During the 1946 General Convention, the governing body officially adopted a seal for the Presiding Bishop using la Rose's design from 1940 as the basis (General Convention, 1946).

|

Seal of the Presiding Bishop

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

Oldham (1946) notes the final version of the Presiding Bishop's seal adopted in 1946 was designed and rendered by retired US Army Major George Moseley Chandler (1876-1961), a former lay member of the Joint Commission on Flag and Seal. Chandler's earliest known work is a coat of arms designed for his fraternity Beta Theta Pi, which the national organization officially adopted in 1897 (Beta Theta Pi, nd). Moreover, it was Major Chandler who successfully aided the Diocese of Washington in officially accepting la Rose's revision of its coat arms later that year (Chandler, 1946).

|

The Anglican Compass Rose by Canon West

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

Among his many contributions towards advancing sound heraldry in the Episcopal Church, the Rev. Canon Edward Nason West, OBE, Th.D., Litt.D., Sub-Prelate St.J. (1909-1990) would create a unifying symbol with his creation of the Anglican Compass Rose in 1954 (Long, 1988). The arms of St. George anchor the emblem in the center and surrounded with the Gospel text from John 8:32 in Greek, "ye shall know the truth." Dedicated during the 1988 Lambeth Conference, the new worldwide insignia for the Anglican Communion was embedded in the floor of Canterbury Cathedral, and later in the floors of Washington National Cathedral and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. West also created new arms for parishes, schools, cathedrals, and dioceses.

|

Arms of Washington National Cathedral designed by Alanson H. Sturgis in the late 1940s

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

During the late 1960s, another retired US Army officer would make significant heraldic contributions through his designs for the church. Col. Harry Downing Temple (1911-2004), former head of the US Army's Institute on Heraldry, was commissioned by Washington National Cathedral to design coats of arms for those Episcopal cathedrals in the US without such ensigns. Temple added 32 new cathedral arms that would be carved in the ceiling of the nave at the National Cathedral (Washington Post, 2004). In addition to rendering arms for schools, colleges, parish churches, and municipalities, Temple created new heraldic identities for the Dioceses of Virginia and Georgia in 1971 and both are still used today (Temple, 1971; Archives of the Diocese of Georgia, nd).

|

Arms of the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

During the 1982 General Convention held in September, a resolution to establish an advisory committee on heraldry was introduced and passed. The text of the resolution seemed promising.

"That the Presiding Bishop be authorized and requested to appoint an Advisory Committee on Heraldry of not less than three persons who have special knowledge and skills in heraldry. The Committee shall serve in an advisory capacity to the Presiding Bishop, Diocesan Bishops and other individuals or organizations seeking advice on seals, crests and other applications of heraldry" (General Convention, 1982, C-75-C-76).

On May 26, 2005, the Rev. Canon J. Robert Wright (1936-2022) presented, "Heraldry of the American Episcopal Church," at the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society and offered insight into the committee's work. According to Wright (2005), the Committee on Heraldry included himself, John P.B. Brooke-Little from the College of Arms, the Rev. Canon Edward N. West from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Col. Harry D. Temple, and chaired by Dr. J. Waring McCrady from Sewanee: The University of the South.

|

Personal arms of the Rev. Canon Edward N. West

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

Wright (2005) notes this committee met only once and never distributed minutes following its meeting. Moreover, there was no published report. During his presentation, Canon Wright provided a summary compiled by Brooke-Little from the committee's sole gathering.

- "Guidelines for the use of heraldry in the Episcopal Church should be written and published

- Bishops should be required to use arms even if other symbols are also utilized

- The bishops’ arms should appear on their diocesan seals with a legend beginning “Seal of the Diocese of ...” at 7 o’clock

- The committee should help with the design of the bishops’ arms, which, in turn, should be registered with the committee after diocesan adoption

- The blazon, or technical description, of the arms, rather than any picture or drawing, is to be the criterion that is followed

- The permissive designs for ecclesiastical hats as laid down by the Earl Marshal of England in 1976 for Anglican clergy should be adopted for clergy below the rank of bishop.

- The use of mottoes should be discouraged

- The use by bishops of a key and crozier behind their arms should be permitted, the key being in bend and the crozier in bend sinister, and both of gold

- Bishops may or should ensign their arms with the mitra preciosa, either gold and jeweled or chased as jeweled with gold infulae (insignia of office)

- The only mandatory ornament exterior to an episcopal coat of arms should be the mitre, of which the infulae are essential

- The color of the lining of the mitre is of no consequence

- Cathedrals should not have arms, but only the bishop as diocesan

- Seals should not be depicted in color and can be of any shape but preferably vesical or round

- In legends on seals the colon should be used for separation, and a full point for an abbreviation

- There should be a manual prepared on flags, banners, etc.

- There should be a set form of approved registration" (Wright, 2005, 7-8).

To read the Earl Marshal's warrant from 1976 regarding ecclesiastical heraldry, please click here. Wright (2005) concluded by stating some of the aforementioned guidelines took hold while many others have not. The noble attempt in 1982 to regulate church heraldry seemingly fizzles and becomes a low priority for the Church.

|

Impaled arms of the Rev. Canon John G.B. Andrew, OBE, D.D. (1931-2014) with the arms of St. Thomas Church in New York City. Andrew was XI Rector of St Thomas.

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

Two examples of clerical arms following the guidance of the Earl Marshal's Warrant of 1976 can be seen above. Three red tassels pendant from a galero indicate the rank of canon, while the red skein found interlacing the chords indicate the armiger's Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) degree. In the US, the degree of Doctor of Divinity is awarded

honoris causa. For Canon West's coat of arms, the red skein indicates that he holds multiple doctoral degrees--one earned and several honorary. Canon Andrew's personal arms are impaled with the arms of the parish he served, illustrating an abstract

marriage between the priest and his parish.

|

Flag of the Anglican Communion

Rendered by Chad Krouse, 2025 |

During the gathering of Anglican Primates from across the communion, the Archbishop of Canterbury inaugurated in 1991 a flag for the Anglican Communion bearing Canon West's compass rose. The flag was produced in 1990 by the Rev. Andrew Bruce Carew Notere from the Anglican Church of Canada (McKnight, 2023 March).

In 1993, the Rev. Canon Eckford J. de Kay (1923-2012) published Heraldry of the Episcopal Church, the only publication concerning Episcopal Church heraldry. De Kay (1993) provides illustrations and design rationales for approximately 600 seals and arms of dioceses, cathedrals, parishes, and other church-related organizations.

Regarding flags in the Episcopal Church, de Kay (1993) suggests an arrangement similar to the Earl Marshal's flag warrant when designing diocesan flags. The illustration above shows de Kay's template using the flag of the Episcopal Church without the crosses crosslet in saltire. The blue dexter quarter, indicating the American branch of the Anglican Communion, would contain the diocese's arms (Temple, 1993, 89).

For those dioceses without arms, de Kay's arrangement might boost whatever insignia used for identification. The blue quarter may likely cause some visual competition for certain diocesan arms whose designs fail to contrast against the background. Many dioceses have well designed and clear coats of arms that would make striking flags. This flag proposal could possibly diminish an otherwise beautiful armorial flag. De Kay's template for diocesan flags is a place to begin when discussing how flags in the Episcopal Church should harmonize with its official 1940 design.

The biggest criticism of De Kay (1993) is the lack of sources citing his data. Based on my review, it appears that De Kay (1993) likely wrote letters to each organization in order to secure emblazonments and information. The work, however, significantly contributes to the body of knowledge regarding Episcopal Church heraldry, but know the information is most likely self-reported and requires additional investigation for source attribution. Without de Kay's work, understanding Episcopal Church heraldry and its impact on the development of an American heraldic tradition would be difficult to compile.

Conclusion

The story of how the Episcopal Church adopted its ubiquitous coat of arms is rather long (precisely 39 years covered here) but filled with interesting actors and minor dramas. The publications on the Episcopal Church's heraldry from 1901-1914 help frame this story, contextualizing the early 20th century American mindset regarding ecclesiastical heraldry. William Baldwin's quest for a national church symbol began in 1918 following his work for the Diocese of Long Island's anniversary, and the layman would see this dream realized by 1940.

Commissions and committees comprised of clergy and laity reflect the governing ethos of the Episcopal Church. While designing seals, flags, or arms by committee is both dangerous and causes unnecessary delays, the structure of the Church demands balance between ordained and non-ordained. This balance of power was incorporated into the Church's constitution and canons and seemingly follows the same spirit found in the US Constitution.

Without the data for la Rose's design in 1919 for the National Student Council and the minutes from National Council's meeting in 1921-1922, it would be impossible to render a guess for the very first design proposed for the Church in 1921. Moreover, as the designs became rendered as flags throughout the 1930s, the Earl Marshal's warrant of 1938 likely played a key role influencing la Rose's final design. In the absence of original images, I have attempted to bring to life the blazons and descriptions found in meeting minutes and convention journals. These images illustrated the numerous proposals which helped get the Church to a place to adopt its final design.

This is the complete and untold story of how the Episcopal Church got her arms based on all known data. I hope these two articles provide a needed contribution towards our understanding of the Church's armorial bearings by filling in gaps to the story. It has been a delight to learn and share all of this rich information, and I simply cherish my church's symbol even more knowing the struggles behind its evolution.

Works Cited

Archives of the Diocese of Georgia. Diocesan emblems. Archives of the Diocese of Georgia, accessed on June 17, 2025, http://archives.georgiaepiscopal.org/?page_id=31

Baldwin, W.M. (1941). History of the church flag. Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, 10(4), 408-409.

Beta Theta Pi. (n.d.). Coat of arms & great seal. Beta Theta Pi. https://www.beta.org/archives-heraldry/

Chandler, G.M. (1946 December). Seal of the Diocese of Washington--1946. Washington Diocese, 5-6.

Cram, R. A. (1901 June 29). The heraldry of the American church. The Churchman, 83(26), pp. 813-818.

Cram, R.A. (1901 August 31). The heraldry of the American church [Letter to the editor]. The Churchman, 84(9), pp. 263-264.

De Kay, E.J. (1993). Heraldry of the Episcopal Church. Acorn Press.

Diocese of Quincy (1906). The 28th annual convention of the Diocese of Quincy. Review Printing Company.

Egleston, C.L. & Sherman, T. (2019 May 19). A flag and a seal: Two histories. In C. Wells (Ed.), The Living Church, 258(9), pp. 16-17.

Fox-Davies, A.C. (1978). A complete guide to heraldry. Bonanza Books.

General Convention (1922). Journal of the 47th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Abbott Press.

General Convention (1925). Journal of the 48th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Abbott Press.

General Convention (1928). Journal of the 49th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Abbott Press & Mortimer-Walling, Inc.

General Convention (1931). Journal of the 50th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Frederick Printing & Stationary Co.

General Convention (1937). Journal of the 52nd General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. W.B. Conkey Company.

General Convention (1940). Journal of the 53rd General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. W.B. Conkey Company, pp. 286-288.

General Convention (1946). Journal of the 55th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. W.B. Conkey Company.

General Convention (1982). Journal of the 67th General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Seabury Professional Services.

Hertell, E.S. (1941). Our church's flag. In C.P. Morehouse (Ed.), The Layman's Magazine of the Episcopal Church, no.15, 14-15.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1907 May). Ecclesiastical heraldry in America. In R.A. Cram (Ed.), Christian Art, 1(1), pp. 64-70.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1907 November). Ecclesiastical heraldry in America II. Diocesan arms. In R.A. Cram (Ed.), Christian Art, 2(2), pp. 59-71.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1914 April 11). Ecclesiastical heraldry. The Living Church, 50(24), pp. 835-836.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1918). Some examples of Catholic corporate heraldry. In H.J. Heuser (Ed.), The Ecclesiastical Review, 58(February), pp. 189-198.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1930 July 19). Letter from Pierre de Chaignon la Rose to the Reverend Sister President of Mundelein College. Unpublished letter.

La Rose, Pierre de C. (1930 December 3). Letter from Pierre de Chaignon la Rose to Ralph Adams Cram. Unpublished letter.

Long, Charles H. (1988). Who are the Anglicans? Forward Movement Publications.

Luce, J.H. (1958). The history and symbolism of the flag of the Episcopal Church. Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, 27(4), 324-331.

McKnight, Gisele (2023 March). My journey there: Andrew Bruce Carew Notere. The New Brunswick Anglican, accessed June 16, 2025 https://dq5pwpg1q8ru0.cloudfront.net/2023/03/01/06/48/04/0051b7ee-9ebc-4a2f-a435-a705635c4d81/MAR2023%20NBAng%20webready.pdf

Morehouse, C.P. (Ed.) (1941 September). The Layman's Magazine of the Living Church, 20, 27.

National Council. (1921a). Minutes from the February 17th meeting of the National Council of the Episcopal Church [unpublished document]. The Episcopal Church, New York, NY.

National Council. (1921b). Minutes from the April 27th meeting of the National Council of the Episcopal Church [unpublished document]. The Episcopal Church, New York, NY.

National Council. (1922a). Minutes from the February 8-9 meeting of National Council of the Episcopal Church [unpublished document]. The Episcopal Church, New York, NY.

National Council. (1922b). Minutes from the May 10-11 meeting of National Council of the Episcopal Church [unpublished document]. The Episcopal Church, New York, NY.

National Student Council of the Episcopal Church (1920 March). 1919 annual report of the National Student Council, bulletin 6. National Student Council of the Episcopal Church.

Oldham, G. Ashton. (1946 May 26). A seal for the Presiding Bishop. The Living Church, 112(21), 12-13.

Slocum, R.B. & Armentrout, D.S. (Eds.) (2000). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A user-friendly reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing, Inc., 174.

Stevens, C.E. (1901 August 10). Heraldry of the American Church [Letter to the editor]. The Churchman, 84(6), pp. 171-172.

Stevens, C.E. (1902 April 5). Anglican Episcopal seals. The Churchman, 85(14), pp. 431-435.

Story, F.W. (1901 August 10). To the editor of The Churchman [Letter to the editor]. The Churchman, 84(6), 172.

Temple, H.D. (1971). Heraldry and the Diocese of Virginia. Privately printed.

The Living Church (1906). Diocesan seal for Quincy. The Living Church, 35(24), 1007.

The Spirit of Missions (1921). Meeting of the Presiding Bishop and council. The Spirit of Missions, 86(3), 182.

The Washington Post. (2004 February 27). Harry Downing Temple. The Washington Post, accessed on June 16, 2025, https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/washingtonpost/name/harry-temple-obituary?id=5501875

Turner, B.W. (2010). Pro Christo Per Ecclesiam: A history of college ministry in the Episcopal Church [Unpublished master's thesis]. Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary in Virginia. https://issuu.com/janus532/docs/cmthesis/19

Whipple, H.B. (1901 July 20). Seal of the Diocese of Minnesota [Letter to the editor]. The Churchman, 84(3), 77.

Wright, J. (1908). Some notable altars in the Church of England and the American Episcopal Church. MacMillan Company.

.PNG)

.jpg)

.PNG)

.png)

.png)